Florida, now the 27th state of the United States, has a rich and complex history of ownership before joining the Union. Its strategic location and abundant resources made it a valuable prize for various European powers. Understanding who controlled Florida prior to U.S. statehood provides insight into its diverse cultural and historical heritage.

Indigenous Peoples Before European Contact

Before European explorers arrived, Florida was home to numerous indigenous tribes, each with its own distinct culture and societal structure. Prominent among these were the Timucua in the northeast, the Apalachee in the northwest, the Calusa in the southwest, and the Tequesta in the southeast. These tribes thrived for thousands of years, developing complex communities and trade networks across the region.

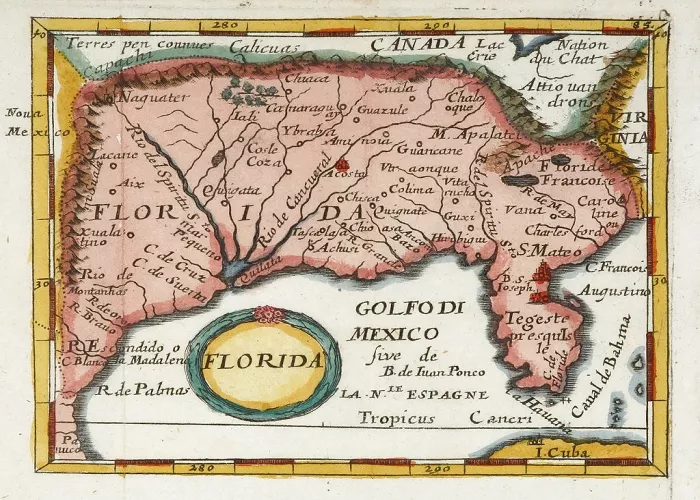

Early Spanish Exploration and Settlement

In 1513, Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León became the first European to land on the Florida peninsula. He claimed the land for Spain, naming it “La Pascua Florida” in honor of the Easter season. Over the next century, Spain established missions and settlements, including the founding of St. Augustine in 1565 by Admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, which is considered the oldest continuously inhabited European-established settlement in the continental United States.

Despite these early efforts, Spanish attempts to colonize Florida faced significant challenges. Expeditions led by explorers such as Pánfilo de Narváez in 1528 and Hernando de Soto in 1539 encountered resistance from indigenous populations and suffered from disease and lack of supplies. These hardships hindered Spain’s ability to establish a strong foothold in the region during the early years of exploration.

French Attempts at Colonization

In 1564, French Huguenots established Fort Caroline near present-day Jacksonville, aiming to create a refuge for Protestants facing persecution in France. This settlement threatened Spanish claims in the area, leading to a decisive response. In 1565, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés attacked Fort Caroline, killing most of the French colonists and solidifying Spanish control over Florida.

British Rule and Division

Following the Seven Years’ War, the 1763 Treaty of Paris ceded Florida to Great Britain. The British divided the territory into East Florida and West Florida. East Florida, with its capital at St. Augustine, encompassed the eastern part of the peninsula. West Florida, with its capital at Pensacola, included the panhandle region. During this period, the British encouraged settlement by offering land grants, leading to an influx of settlers from other British colonies.

The British period also saw improvements in infrastructure and the economy. Plantations were established, and efforts were made to cultivate crops such as indigo and sugarcane. However, Florida remained sparsely populated compared to other British colonies, and its development was limited by challenges such as conflicts with indigenous tribes and the harsh environment.

Return to Spanish Control

In 1783, after the American Revolutionary War, Britain ceded Florida back to Spain. Spain maintained control over the region, with East Florida and West Florida as separate colonies. However, Spain’s ability to govern effectively was limited, leading to conflicts with American settlers and Native American groups.

During this second Spanish period, Florida became a refuge for runaway slaves and displaced Native American tribes, including the Seminoles. The Spanish authorities’ relatively lax control over the territory allowed these communities to establish themselves, leading to a unique cultural blend in the region. However, this also resulted in tensions with neighboring American states, particularly Georgia, where settlers were concerned about the sanctuary Florida provided to escaped slaves.

American Expansion and Acquisition

The early 19th century saw increased American interest in Florida. In 1810, American settlers declared the Republic of West Florida, seeking annexation by the United States. By 1812, the U.S. had incorporated most of this territory. Simultaneously, conflicts with the Seminole tribe and runaway slaves seeking refuge in Florida led to the First Seminole War. Unable to effectively defend the territory, Spain agreed to cede Florida to the U.S. through the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819. The transfer was completed in 1821.

The acquisition of Florida was driven by several factors, including the desire to eliminate the refuge for runaway slaves, to end the threat posed by Seminole raids into Georgia, and to gain control of strategic ports and lands for American expansion. The U.S. government also sought to prevent other European powers from establishing a presence in the region, aligning with the broader goals of the Monroe Doctrine.

Conclusion

Before becoming a U.S. state, Florida was controlled by several European powers. Spain’s early exploration and settlement laid the foundation for its long-term influence. British rule introduced new settlers and divisions within the territory. Spain’s later return saw continued challenges in governance. Ultimately, American expansionist interests led to Florida’s acquisition by the United States. This history has left a lasting impact on Florida’s cultural and demographic landscape.